Note: For the sake of simplicity, I will be using the term ‘modern art’ to mean anything from 1850 and onwards to the present— this includes fauvism, cubism, dadaism, surrealism, postmodernism, contemporary, and conceptual art. Thus, I will be discussing artists ranging from the likes of Picasso, Rothko, and Duchamp all the way up to the present because they’re usually who people refer to when they say “modern art”, not the Impressionists or Cézanne or Monet.

When I first started my IGCSE art course in 2018, one of our first projects was to recreate one of Picasso’s Proto-Cubist artworks— I don’t exactly recall which, but it might have been “Brick Factory at Tortosa”. There was a flurry of outrage in response to the assignment. As arrogant fourteen-year-olds, we were offended that the teachers went out of their way to pick what seemed like the ugliest, plainest, and most unchallenging piece of work for us to recreate.

Of course, the piece was only deceptively easy; my pride and belief in my artistic talents were dealt a heavy blow upon the discovery that I could not, in fact, replicate the precise brush strokes, the exact browns, and the wonky perspectives Picasso had employed. It was a humiliating state of affairs. When we realised the curriculum entailed exercises like drawing our partner’s face without pulling the pen off the paper, we felt duped. I suppose we were under the impression that we’d churn out the next “Mona Lisa” or something, but even after the course, the rest of us would frequently complain about the inadequacy of that class and how we didn’t “learn” anything. Now, as I reflect on my fourteen year old self from seven years ago, I finally understand that my teachers were trying to teach us a lesson— a lesson which I’ve only unfortunately understood the full gravity of years later.

There’s a lot of controversy surrounding the very existence of modern art, from videos of people at modern art museums standing beside pieces that they think they could recreate to tweets lamenting the existence of the ‘banana on the wall’. These always generate mixed responses on the internet; there are many who frown upon modern and contemporary art, accusing them of being insults to “real art”, whilst others staunchly defend these movements with fervor. I myself fall into the latter category, despite them being far from my favorites in the timeline of art history. The reason for this stems from an underlying question I ask everyone who says they don’t consider modern art “real” art— “what does it mean for something to be art?”

I, too, sneered at modern art for a very long time, but that changed with my growing disillusionment with realism and hyperrealism. I used to paint a lot, but the only thing I was putting into those pieces was time and some (questionable) technical skill. Beyond that, I felt like a copier machine lacking any true agency or creativity. The hyperrealism that I was always told was the paragon of artistry lacked messaging and seemed to place a greater focus on the artist’s merit than a conversation between the artist and the viewer. Of course, I still respect realism, because technical skill can be an important facet of art. This is why teachers emphasise elements of art such as line, shape, space, value, form, texture, and colour, through realism first. One should have an understanding of the thesis before they come up with an antithesis. All this said however, a lot of hyperrealism did not evoke emotions in me beyond “the pencil work looks amazing!” and “this must have taken them loads of time!” It was this precisely this that got me into modern art in the first place.

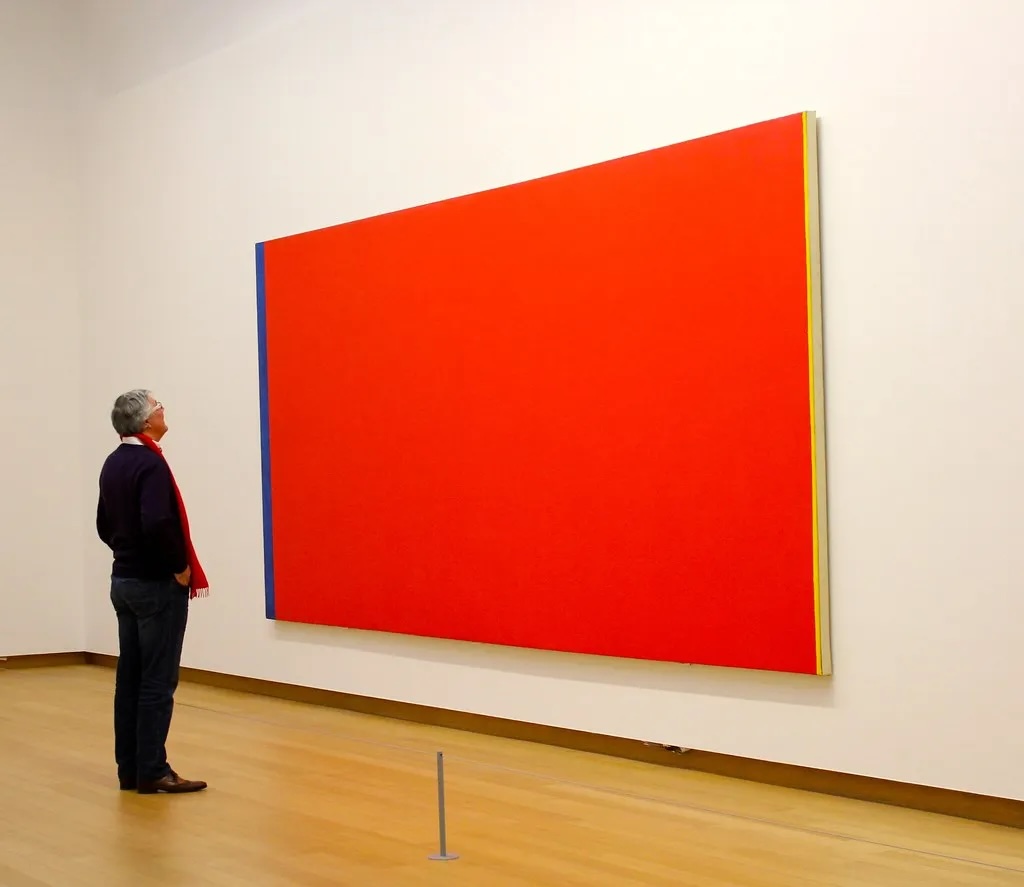

There was something to it beyond stimulating my visuospatial sketchpad; it challenged my very preconceptions of what it means for something to be art. When I visited New York two years ago, I got to see Barnett Newman’s “Vir Heroicus Sublimis” in person at the Planes of Color exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. “Man, Heroic and Sublime”. I could not tell you what compelled me to be overcome with emotion to the point of standing in front of it for ten minutes straight, but I would’ve honestly stayed there longer if I wasn’t ushered to move along by my (understandably) irritated family.

“Modern art is ugly” is probably the most common sentiment that come from dislikers. My gripe with this is that this argument derives from placing utmost importance to aesthetics beyond all else in art. What makes something beautiful anyways? Moreover, who gets to define it? There are often very narrow ideals of what “beautiful” means and this changes decade to decade, so how can we call modern art ugly? There was a time where Van Gogh’s now universally loved “The Starry Night” was considered ugly in comparison to, say, “Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring”. Yet now, as we look at them we can appreciate both very different styles of art.

I think the most important question however is, “does art have to be beautiful to be considered art?” This hails back to one of those unanswered questions of time immemorial: what constitutes art? There’s a general consensus that art is meant to evoke emotion; many would argue that beauty and aesthetics play a major role in this, while others believe that those factors are completely irrelevant— at least in the present day with the advent of photography. After all, that’s what the modernists and post-modernists were trying to do– play with, twist and break the boundaries of what art is. Does something even have to be inherently be considered beautiful to be considered art?

The root of the matter lies in what Lucy L. Lippard coined the “Dematerialization of art”[1]. A common criticism of modern art is that nothing is straight-foward anymore: why must it only make sense after it has been explained? However, in these works, the artistry is meant to lie in the idea, rather than just the physical medium that conceives it. It places just as much emphasis on the process of creation as it does the result, which creates a deeper dialogue between the art and the artist, instead of only the art and the viewer. The outcome is a richer network that link the art, the artist, and the viewer.This is a rejection of art as merely visual, and instead embraces it as a form of intellectual enquiry, which is precisely why its followers are labeled as ‘pretentious’.

However, It also begs the question: “does art even exist anymore?” After all, the implication of dematerialization is that anything can be considered art.

So, what defines art? Some state that art must elicit an aesthetic experience, so if this was universally accepted, then:

p is sufficient for q.

p is necessary for q.

where:

p is aesthetic experience.

q is art.

However, this creates a problem where we end up significantly broadening the definition of art, because anything that fulfills the preceding conditions is now classified under the definition, like that really beautiful bird you saw at the beach, or the wine stain on your dress that looks like a dragon. So we then stumble into the original problem because if beauty is in the eye of the beholder, what might be an aesthetic experience to one may not hold true for another. Therefore, anything could constitute art, and we’re back to square one.

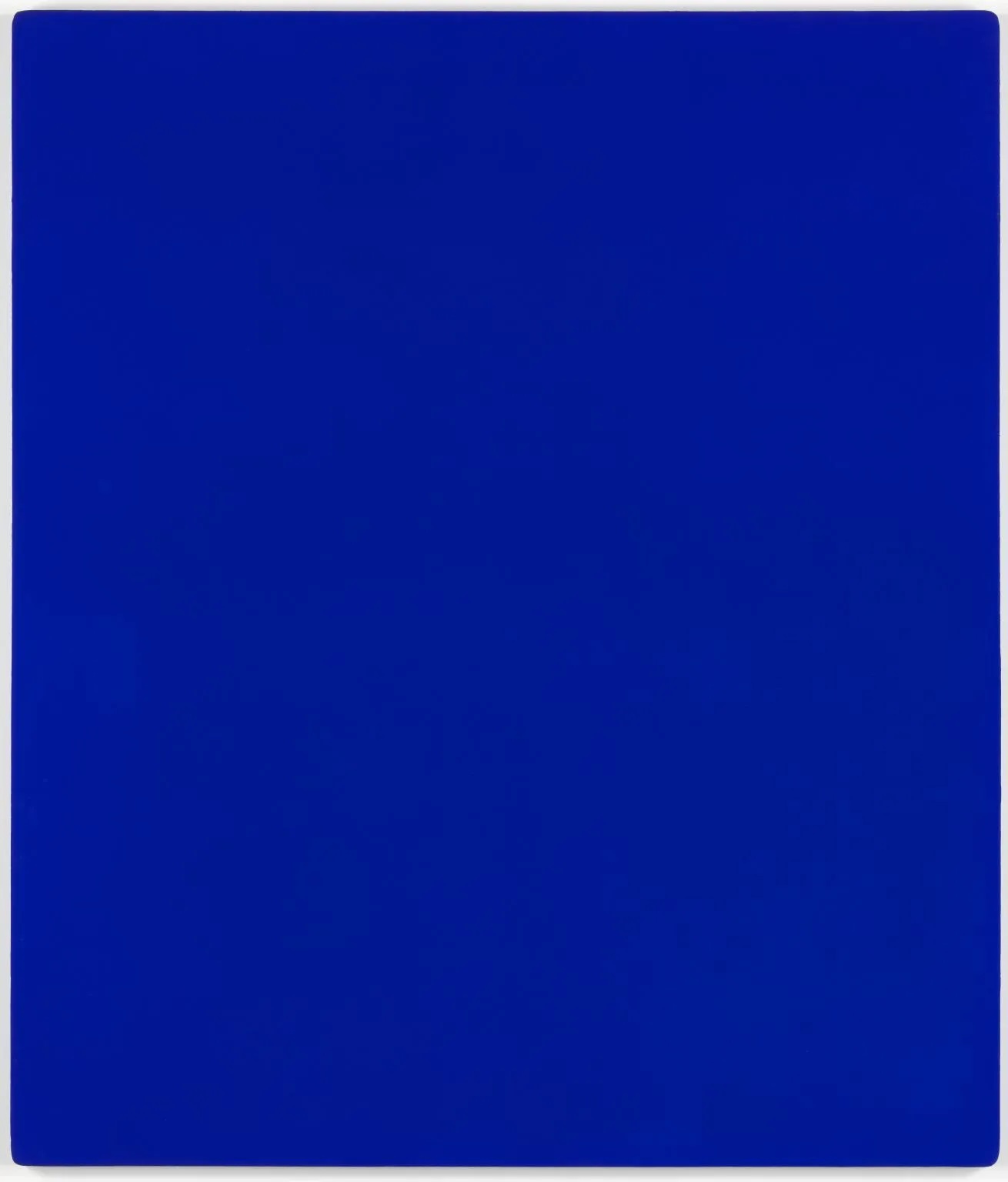

So then, we may explore another argument against modern art, which questions the skill required to create them in comparison to other styles. The flaw in this argument lies in the fact that it simply does not apply to modern art. This is because realistic art has a very clear end goal, which is a precise imitation of the reference. As modern art does not have such a clear endpoint, it’s very easy for viewers to note that “a five year old could have also made this”; they presume that the same aforementioned standards also apply to modern art, and therefore modern art fails to meet their standards. Jacob Geller made an exemplary video essay about this titled “Who’s Afraid of Modern Art”[1], in reference to Barnett Newman’s “Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue?”. This painting was heavily criticised when it was first displayed at the Museum of Modern Art and was vandalised and slashed across the canvas numerous times, ironically answering the very question it posed. The Museum’s attempts to simulate Newman’s technical precision of the brush strokes and replicate the exact colours that Newman had used to paint it were futile. Likewise, IKB 79 by Yves Klein is a painting often used to degrade the replicability of modern art— after all, it is just blue on a canvas. Yet upon further introspection one would come to realise that Klein actually invented this shade of blue in the paint medium, which negates the argument of skill, or the lack thereof.

None of these arguments matter really, because the infamous banana on the wall was installed in 2019, and people are still talking about it six years later. Our participation is a part of the piece itself; it stimulates discussion and discourse and feeds into the everlasting conversation of what constitutes art, therefore fulfilling its intended purpose. Pushing the boundaries of art is precisely what leads to the emergence of more art! Especially with the emergence of advanced AI models that can create hyperrealistic “art”, we need to find new ways to express the human condition. After all, life is becoming increasingly absurd, so why shouldn’t our art reflect that? So what if art actually requires you to read the plaque next to the frame in the gallery? It’s not the artist’s fault that you were busy drawing eyes in the margin of your notebook when your teacher was going over media literacy. This is why certain political parties of the 20th century were so adamant on hastening the return to “classical art” and the implicit aesthetic values they portrayed, be it the ‘golden age’ of European civilisation or the prowess of Christendom. They saw the likes of Expressionism, Cubism, and Dadaism as signs of amoral degeneracy, and they despised the questions that modern art dared to ask. (This topic requires a whole other essay, so I’ve linked one).

You are by no means a terrible person just because modern art is not up your alley. But like it or dislike it, modern art is real art. Go ahead and splatter paint on a canvas in rebellion and sell it for one million dollars to make a point that “modern art is a scam”—likely, no one will buy it because it’s unoriginal and derivative, but that doesn’t make it not art. And as much as I can’t stand photorealistic pencil drawings of puppies and old people, I don’t have any right to define what constitutes art— nobody does. And that’s kind of the whole point.

Footnotes