I was first introduced to the concept of intertextuality in my morning English Literature class in Sixth Form. I vividly recall entering that classroom for the first time, gripping a huge mug of coffee in a desperate attempt to stay awake and warm amidst the throes of autumn. My English teacher at the time was a somewhat pretentious American who always wore a thick scarf around his neck and claimed to be a New Yorker. He droned on about the importance of this “intertextuality” for an entire week’s worth of class; it was supposedly the essential pillar of Literature as a structure, yet I found it difficult to care any less. As an opinionated sixteen-year-old, all I wanted to do was get started on discussing the readings we were assigned to complete and maybe show off my close reading abilities.

After all, the concept of intertextuality seemed fairly simple. Books were inspired by other books. Obviously. I didn’t see the value in constantly drilling this concept into our heads, especially through our readings where he’d force us to find a link between two seemingly unrelated texts—who cared if City of Glass by Paul Auster was modelled after Don Quixote? And why did we have to spend an entire month dissecting Carole Ann Duffy’s The World’s Wife Anthology and its plethora of references to biblical/mythical/historical/fictional tales?

This teacher argued that every work of literature ever released was inspired by the ones that came before it. This intertextuality was apparently what made the western literary canon so indispensable, because most of the contemporary texts that exist now (in English) were all somewhat inspired by this canon—The Bible, The Iliad, Shakespeare—you know the type. Subsequently, many of us voiced complaints against the diversity (or lack thereof) of the types of authors we were given to read. He listened to our concerns, but instead of removing the authors as initially planned, he simply added more diverse authors that spanned gender and race.

(We ended up not reading most of them anyway due to the pandemic halting all modes of proper education for a quick minute. But I digress.)

The system of education is rapidly changing, and we live in a world where marginalized people bravely carve out spaces in previously white-heteronormative-male dominated structures like the literary sphere, despite facing much discrimination and struggle. As these authors weave themselves into the fabric of the history of literature, the conversation shifts towards the question of relevance regarding the “classics”, which are often conflated with the Western literary canon. Rife with racism, xenophobia, and misogyny, there’s a reason many argue in favour of these texts being removed as “essential” readings for high schoolers and college students. Who needs Dickensian verbosity anyways? And why should we care about The Great Gatsby when a quick SparkNotes skim will do the trick? Especially when these texts display a copious use of derogatory slurs and prejudices, one can see why there is an increasingly loud call for these texts to be removed from bookshelves and replaced by authors of identities that haven’t had the chance to be represented throughout mainstream literature.

This call for changes to the western literary canon has been criticized by many, often old-age conservatives who place a high value on the supposed “glory” of the European tradition. Most famously, Harold Bloom, in his work “The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages” criticizes the School of Resentment (Lacan, Derrida, Foucault, and the like) who, according to him, use their theories of post-structuralist, feminist, and African-American literary theory to prioritize the goal of literature as being a tool to promote wider ideas of society and politics, rather than a simple expression of aesthetic value.

It should be obvious by now that I am not writing from a place of objectivity, and that I do agree with the post-structuralists for the most part. Therefore, it would come as a surprise that I somewhat reject the abolition of the literary canon, or the “classics”, from school and university curricula. Not for the reasons that an old geezer like Bloom would argue ((bla bla bla School of Resentment everything is so #woke why are we promoting political and social activism instead of aesthetic values—IDGAF), but because whilst he posits that the only valid relationship remains the one between writer and reader, I firmly hold the stance that there are four main parties in the matter: the reader, the writer, society of the writer’s time, and society of the reader’s time. Even if these “classics” don’t appeal to one’s own aesthetic senses, there is great merit in reading them anyway, solely for the way it enables us to interact with the society of the writer’s time— an opportunity contemporary novels do not provide us.

Why is it so important to interact with the societies of Nietzsche or Hemingway or Joyce, you may ask.

You see, to completely understand the systems we exist in the modern day and how we got here, it is, in fact important to read the works of these Western authors because whether we like it or not, these Western cultures colonized the entire world, and we exist in the context of the society that they have forcefully created. These texts give us valuable insight into the European consciousness and how they were shaped to eventually commit the atrocities it did. The western literary canon thus continues to affect us in the present day: a) directly by its impact on our modern-day culture, and b) indirectly, its influence on our modern-day literature, which then influences us through our consumption of it. The impact of the literary canon is undeniable; even if you aren’t big on reading, a lot of these texts have seeped into the very essence of modern culture. Yes, a lot of the literary canon is extremely misogynistic, racist, xenophobic, and homophobic— but why must we grant these authors the grace of forgetting them and letting them rest in the past? I think of Rudyard Kipling and his poem “The White Man’s Burden” about the annexation of the Philippines as I write this—he was raised in British India—he thought it was the white man’s moral obligation to civilize the “others” of the world, and that includes my people who were exploited under the British Raj under the name of economic progress. Why must we forget the atrocities these very cultures committed against our forefathers? These classic texts remain some of the most credible proof of the psyche of those engaged in these moral wrongdoings. I firmly believe that it is far more productive for our collective culture to continue to critically engage with these texts, and while I deeply empathize with the discomfort and pain it may cause to read firsthand prejudices in these texts, I don’t see how turning a blind eye is any better. The truth remains that we have not completely solved the societal issues these books represent as a society. If misogyny, homophobia, and racism were completely eradicated from humanity, I could see the logic in leaving these texts in the past to rot. However, the reality is, these issues persist, and these books remain a vital source in our understanding of how these issues are ingrained throughout our history as a people.

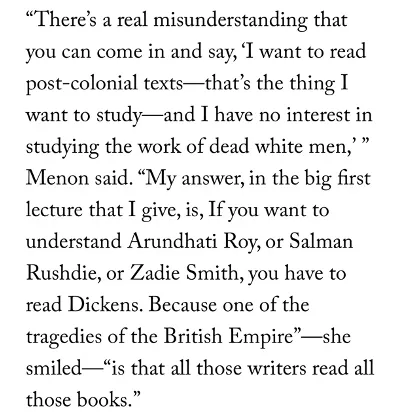

Something Professor Tara K. from Harvard stated in this New Yorker article about the death of the humanities struck a chord in me:.

At the very least, so much of modern media all over the world is drawn from these classics that it is somewhat beneficial to read the source they were inspired by. A few months ago, I went to a queer Black adaptation of Hamlet called Fat Ham. It was a refreshing take on the original script, but a large part of its humor relied on knowing the original tale of the Danish prince. Whether it’s HBO’s Succession that contains Shakespearean themes, or Iyyobinte Pusthakam (ഇയ്യോബിന്റെപുസ്തകം) that nods to the Brothers Karamazov, it becomes very clear that a lot of what we consume now is deeply inspired by these classics.

To take it one level deeper, however, we must ask ourselves, why are there some texts from this Western literary canon that are repeatedly recontextualized into different cultures that span time and space? Perhaps the answer we may not like to hear is that many of them speak to a universality in all of us, something about the human condition that transcends language and culture. For a long time, I was resistant to the classics and begrudgingly read them in anticipation of stuffiness and boring, long sentences. So imagine my pleasant surprise when I read Crime and Punishment for the first time and found myself openly laughing out loud numerous times at Dostoevsky’s wit and dry humor, or reading Voltaire’s short stories and being floored at how clever his satire was.

Granted, one could argue that we should replace these texts with those of people who faced the brunt of the discrimination and prejudices that the authors of these works committed. The reason many folks criticize the Western literary canon is because of the blatant gap in perspective, which is valid. In the process of eliminating them from our cultural consciousness and removing them from our bookshelves, we will only end up creating new gaps, will we not? I want to make clear that I am not saying that we should just make all undergrads and high schoolers only read Of Mice and Men and be done there. I simply believe that reading and the attitude towards the literary canon should be additive and not subtractive — rather than replacing these dead white men, we must add new authors to the list that are of marginalized identities and expand it. (Of course, this comes with the need for a massive overhaul of the education system, but with the rise of anti-intellectualism, shorter attention spans… well, godspeed).

In my part-time job as a writing facilitator, we emphasize essays to focus on the authors of texts being “in conversation” with each other. How would 1984 (George Orwell) respond to IQ84 (Haruki Murakami)? How would the protagonist of the Idiot (Elif Batuman) respond to the protagonist of the Idiot (Fyodor Dostoevsky)? How would Chinua Achebe respond to Joseph Conrad, and why does the title of his most famous work, “Things Fall Apart,” derive from Yeats’ poem The Second Coming?

Doing this, in my opinion, is imperative to reconciling with our past. By connecting works that span time and space, we can truly re-examine all that came before us and explore what is due to come after us. You know how the saying goes: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”. Besides, there is also nothing stopping us from expanding the literary canon to include the works of Toni Morrison or James Baldwin, for instance. At the end of the day, there might be some value in looking back and critically engaging with these so-called literary “greats,” and who knows, we might be surprised by what we find out about ourselves in the process.